Castel Sant’Angelo History – From Hadrian’s Mausoleum to Papal Fortress & Tosca

Hadrian’s tomb reborn as papal fortress: sieges, the plague legend of St. Michael, the Passetto corridor, the 1527 Sack, famous prisoners, Farnese art, and the Bridge of Angels.

Castel Sant’Angelo is a palimpsest in stone: an imperial tomb swallowed by bastions, crowned by an angel, threaded to the Vatican by a secretive corridor, and immortalized by opera. Walk its ramp and you spiral through 1,900 years of memory.

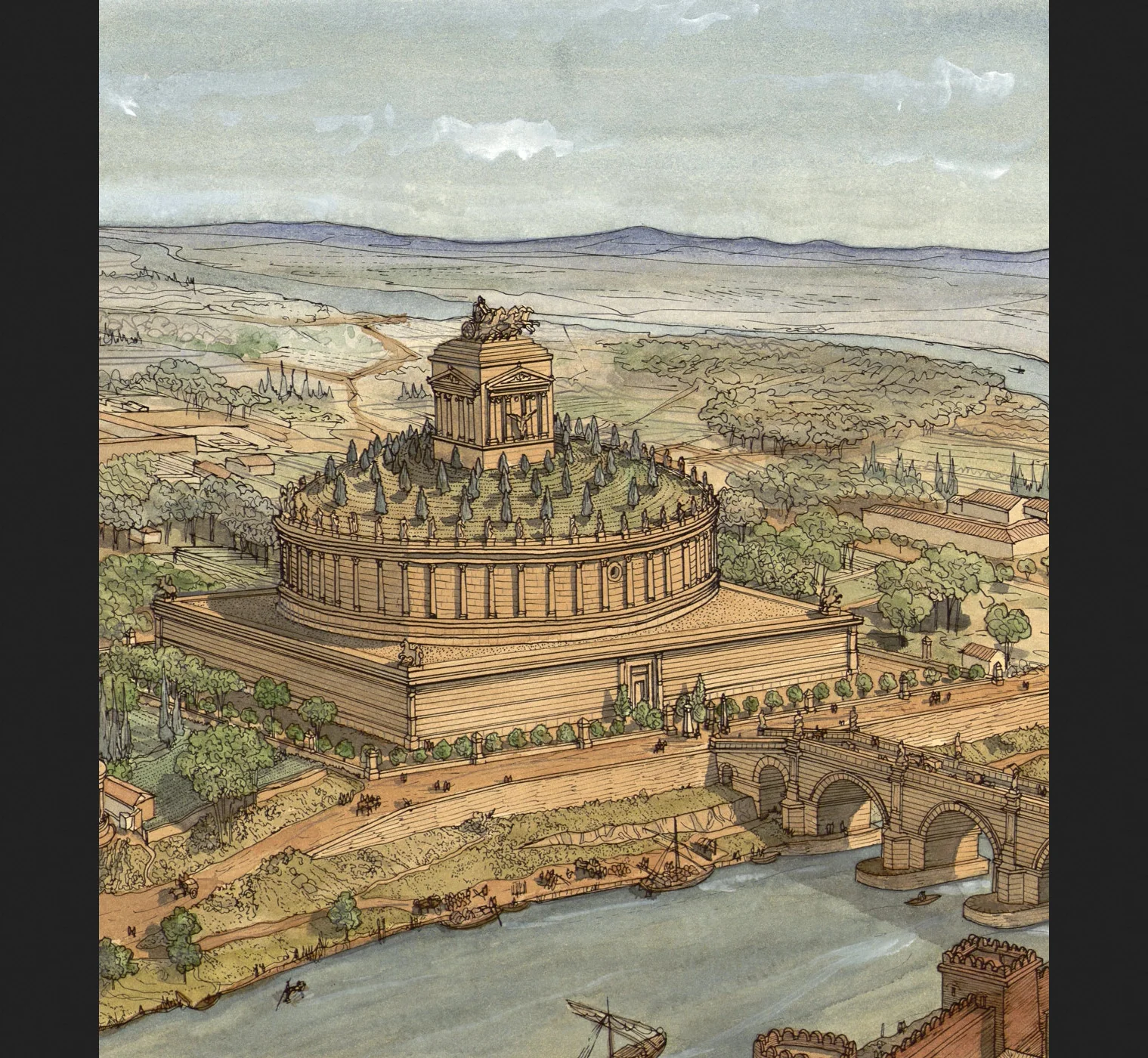

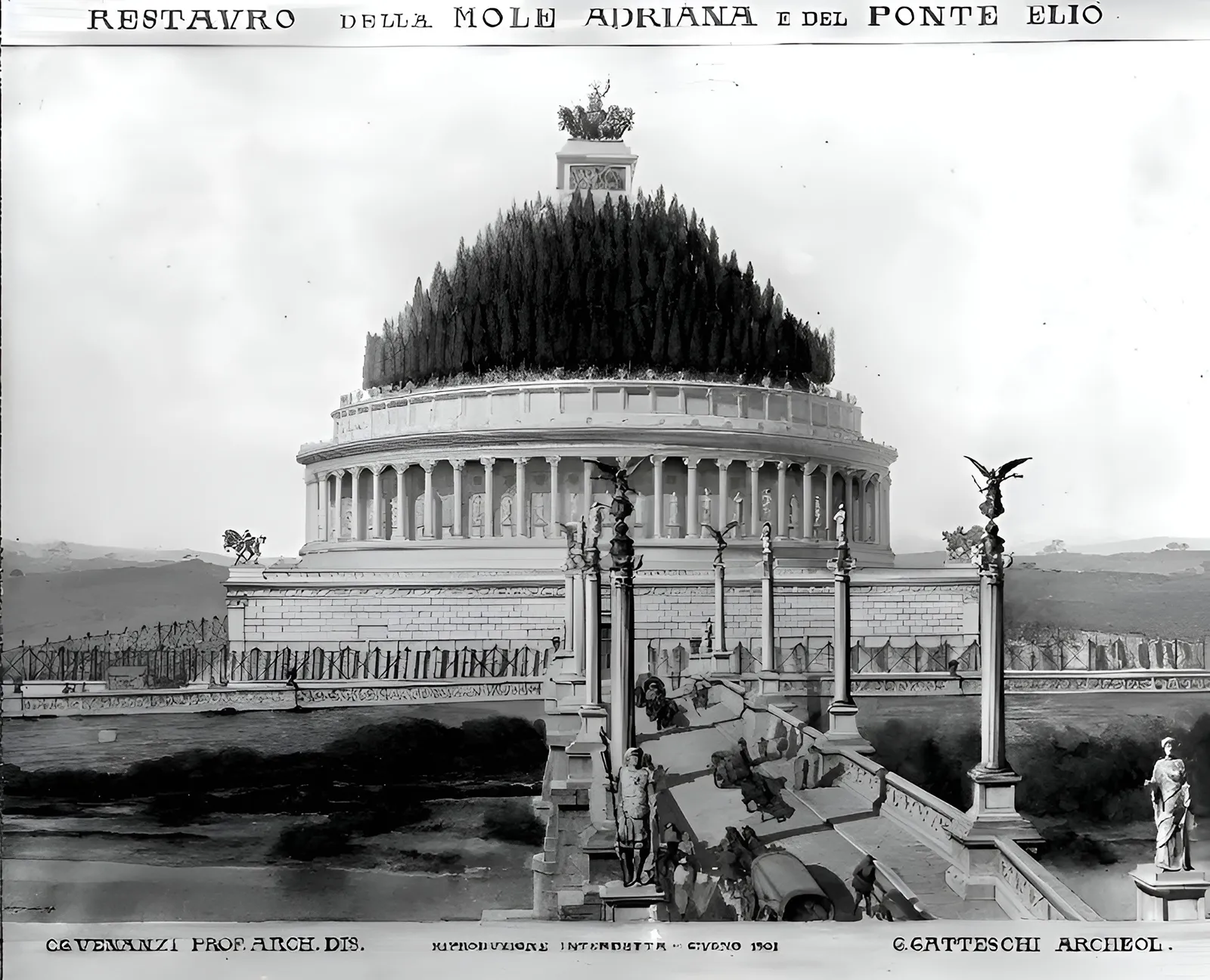

Hadrian’s round mausoleum once carried a gleaming statuary crown—imagine a golden quadriga riding the skyline.

Hadrian’s round mausoleum once carried a gleaming statuary crown—imagine a golden quadriga riding the skyline.

Hadrian Comes Home (134–139 CE)

At 59, after years roaming the Empire, Hadrian returned to Rome determined to shape his legacy. He adopted Antoninus Pius and commissioned a great circular mausoleum on the Tiber’s bank—respecting Augustus’ precedent in scale, but amplifying decoration. Work began around 135 CE; Antoninus completed it in 139, a year after Hadrian’s death.

- Core idea: a cylindrical drum atop a square base, with a helical ramp choreographing the funerary ascent.

- Lost splendor: ancient reports and later reconstructions point to a gilded quadriga with Hadrian as charioteer crowning the summit.

- Dynasty within: ashes of emperors and kin rested here till the early 3rd century; Caracalla is traditionally the last (217 CE).

From Sanctum to Stronghold (3rd–6th c.)

As Rome’s tides turned, usefulness preserved the monument. With Aurelian’s wall circuit (270s) embracing the city, the mausoleum’s position by the river and bridge became strategic. When sieges pressed, the tomb evolved into a bastion.

The funerary drum became the anchor for later defensive rings and artillery platforms.

The funerary drum became the anchor for later defensive rings and artillery platforms.

Plunder and Improvisation

- 410 CE: Alaric’s Visigoths breached Rome; urns were smashed, ashes scattered—centuries of imperial memory lost in days.

- 537 CE: During Vitiges’ assault, defenders hurled statues and marble fragments from the heights, turning art into ammunition, as Procopius recounts.

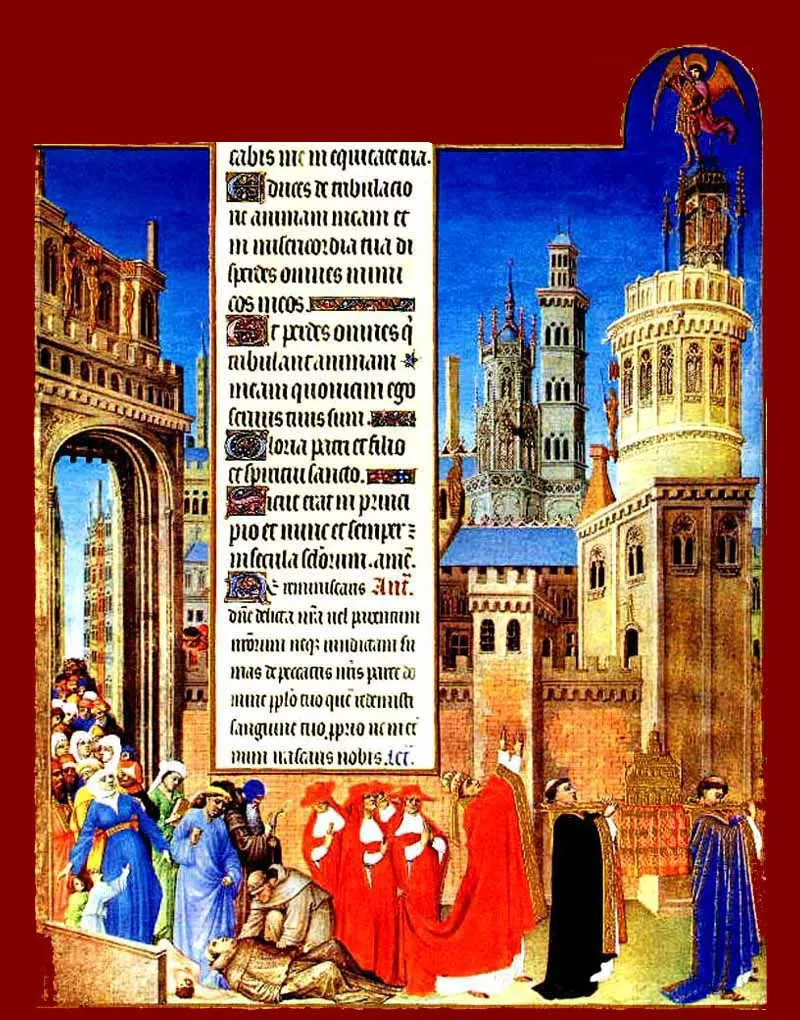

The Angel and the Name (590 CE)

In a city ravaged by plague, Pope Gregory I’s penitential procession passed the old mausoleum. Tradition holds that the Archangel Michael appeared above, sheathing his sword—a sign the pestilence had ended. The name shifted: Castel Sant’Angelo, the Castle of the Holy Angel.

Mercy after wrath: Michael’s sheathed sword became the city’s hope and the castle’s emblem.

Mercy after wrath: Michael’s sheathed sword became the city’s hope and the castle’s emblem.

Six Angels Over Centuries

- Wood (weathered away) • 2) Stone (destroyed in 1378 unrest) • 3) Marble with bronze wings (lost in a storm) • 4) Bronze (melted into cannon during crisis) • 5) Montelupo’s marble with bronze wings (1536, now in the courtyard) • 6) Verschaffelt’s bronze (1753), the angel you see today.

Corridor of Escape: The Passetto di Borgo

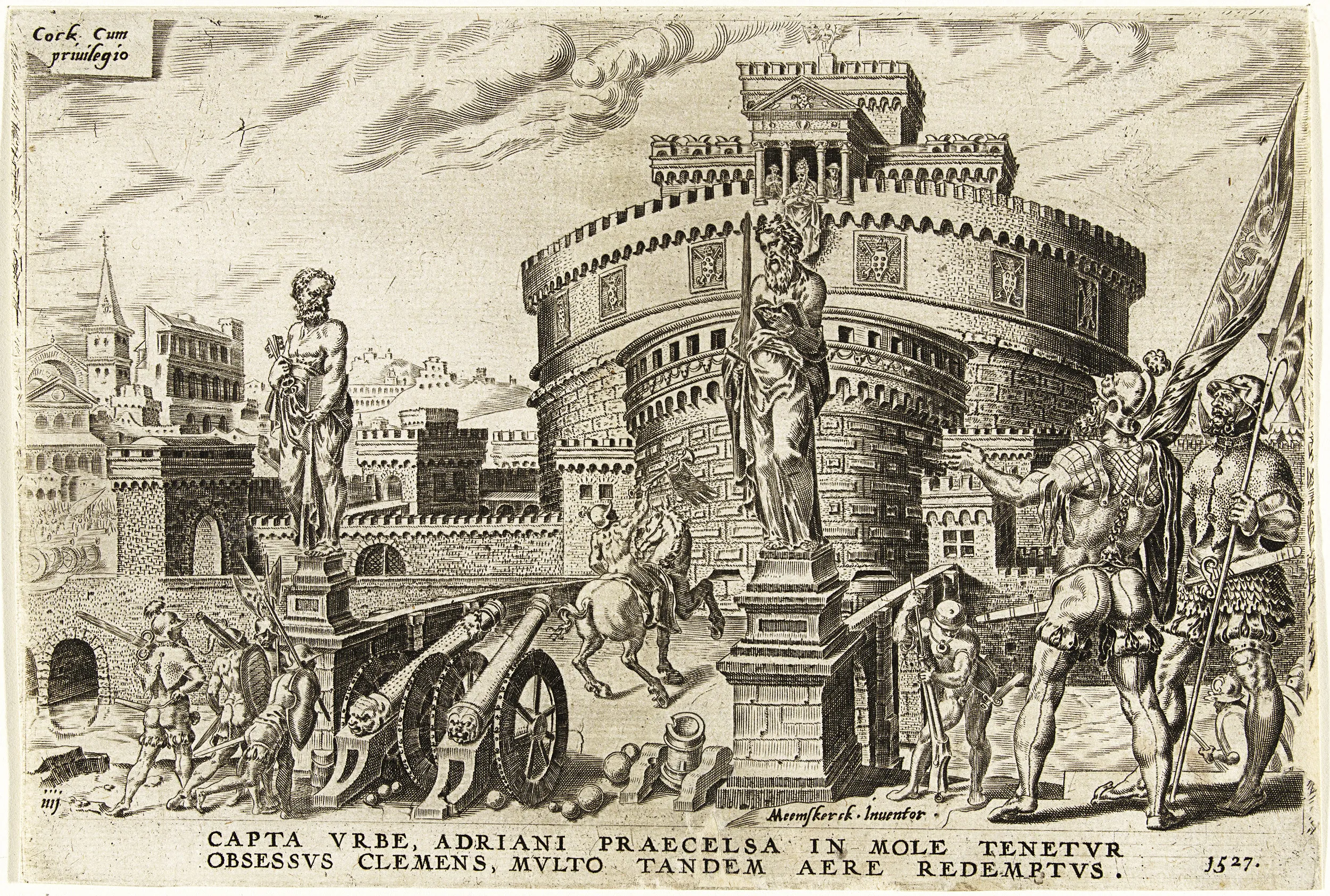

By the 13th century, papal Rome hardened its defenses. Nicholas III conceived the covered corridor—the Passetto—linking the Vatican precinct to the fortress. It proved its worth when Alexander VI fled the French in 1494 and when Clement VII escaped the chaos of 1527.

An elevated lifeline in brick and fear: the papal route to refuge.

An elevated lifeline in brick and fear: the papal route to refuge.

Renaissance Teeth: Bastions, Moat, Cells

From Boniface IX through Nicholas V to Alexander VI (Borgia), Castel Sant’Angelo acquired artillery foundations, crenellations, towers, stores for siege survival, a moat, and prison cells. The round tomb became a modern fortress.

Gunpowder age logic: angled bastions and casemates bite into the drum’s serenity.

Gunpowder age logic: angled bastions and casemates bite into the drum’s serenity.

1527: A City Unmade

Unpaid imperial troops under Charles III tore Rome apart. Churches and palaces were emptied, libraries ransacked, bodies left to rot. The population collapsed from ~55,000 to under 10,000 within months. Clement VII survived via the Passetto and holed up in the castle; outside, civilization smoldered.

Cells, Escapes, and Legends

Castel Sant’Angelo’s prison ledger reads like a mirror to power.

- Benvenuto Cellini—goldsmith, soldier, raconteur—attempted escape by a rope of bedsheets from an upper apartment; the fall broke his leg and deepened his legend.

- Count Cagliostro—alchemist, forger, celebrity—enjoyed a plush loggia before flight, recapture, and death.

- Popes in peril: Stephen VI, Leo V, John X, Benedict VI, John XIV—centuries before modern legal norms, papal Rome could imprison and silence even its own.

Thick masonry, narrow light: isolation weaponized.

Thick masonry, narrow light: isolation weaponized.

A Palace in a Citadel: The Farnese Rooms

Under Paul III Farnese, artists Perin del Vaga and Pellegrino Tibaldi dressed chambers in fresco and stucco. The Sala Paolina stages papal authority with classical echoes; trompe‑l’oeil jokes wink from door panels. Nearby, the Stufetta of Clement VII—with hot and cold water—whispers of Renaissance comfort in a siege refuge.

Diplomacy and display behind walls built for cannons.

Diplomacy and display behind walls built for cannons.

The Bridge of Angels

Hadrian’s Pons Aelius preceded the tomb to ferry building stone. Later renamed Ponte Sant’Angelo, it became the grand approach to St Peter’s. Jubilee crowds once surged dangerously over it; in the 17th century, justice displayed severed heads between angelic statues. Bernini designed the program of ten angels with Instruments of the Passion; copies of his two originals stand on the bridge today.

Angels as chorus, river as orchestra—Rome’s overture to the castle.

Angels as chorus, river as orchestra—Rome’s overture to the castle.

A Scar of Unification

In 1870, a cannonball struck one statue base during the battles of Italian Unification. The mark remains—seek it as a small crater in marble: history in a fingertip.

A small wound that tells of a country becoming one.

A small wound that tells of a country becoming one.

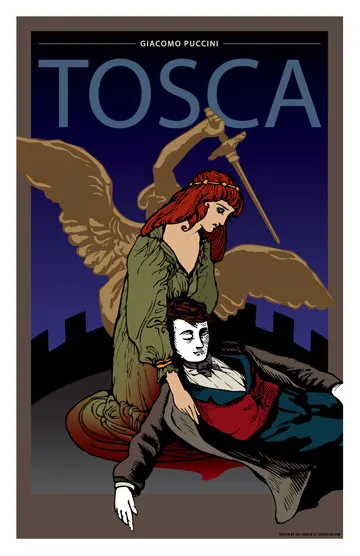

Tosca at Dawn

On 14 January 1900, Puccini’s Tosca premiered. Act III unfolds atop the castle: a false promise of clemency, an execution at dawn, and Tosca’s leap from the parapet. Art fixed the fortress forever in the world’s imagination.

Opera’s tragedy framed by bastions and angels.

Opera’s tragedy framed by bastions and angels.

How to Read the Stone Today

- Trace the helical ramp: funerary choreography turned visitor path.

- Watch the angel at golden hour—mercy silhouetted against the sky.

- Find the seams: Hadrianic core vs Renaissance skins; papal apartments vs gun platforms.

- Stand on the bridge and listen—the city’s past still hums over the Tiber.

Bottom Line

Castel Sant’Angelo endures because it adapts. Tomb, bulwark, prison, palace, museum—each layer remains legible. Come for the view; stay for the echo of centuries.

About the Author

Telmo Rolando

I wrote this guide to help you explore Castel Sant’Angelo with confidence — clear tickets, smart routes and the highlights you shouldn’t miss.

Tags

Comments (0)

Loading comments...